Although the vast majority of Minoan antiquities are visible in Heraklion Archaeological Museum and the other museums on the island of Crete itself, the Ashmolean Museum holds the most comprehensive collection outside Greece. This collection was largely established by one man, Sir Arthur Evans, and is focused on the archaeological site with which he is closely associated: Knossos. Visitors to the Museum can see the highlights of this collection in the Aegean World gallery. Museum staff are also working to make these objects and their associated archive accessible online, so they can be viewed from anywhere in the world. The Aegean World gallery was opened in 2009 as part of a major refurbishment of the Ashmolean Museum.1

Although best remembered for his excavations at Knossos, Sir Arthur Evans was also the Keeper of the Museum from 1884–1908. The Ashmolean Museum opened to the public in 1683 – the first museum of its kind in Britain – but it was Evans who oversaw the collection’s move to its present location. The grand neoclassical building on Beaumont Street in the centre of Oxford, designed by Charles Robert Cockerell, was originally the University Art Galleries. In 1894 the collections were merged to become the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology. This project took up much of the first ten years of Sir Arthur Evans’s time as Keeper; it was only after this work was completed that he made his first visit to Crete.2

One of Evans’s aims in visiting Crete was to build up the Ashmolean collection. He had been brought up with coins and antiquities from an early age since his father, Sir John Evans, was a gentleman scholar who had made important discoveries of prehistoric stone tools and served as President of the Society of Antiquaries. The family paper business provided the wealth to allow both father and son to accumulate personal collections of antiquities, and later to finance the excavations and restorations at Knossos. After a collecting trip to Athens in 1893, Arthur Evans became interested in seal stones bearing what looked like a prehistoric script. These, he established, originated in Crete, and so he became determined to visit. His later excavations at Knossos uncovered further evidence of this script, as well as the clay sealings that preserved impressions of similar seal stones used for recording transactions.

Between 1894 and 1899 Evans travelled around Crete, at times witnessing the aftermath of violence between the Christian and Muslim populations of the island. A former journalist, he often sent reports to British newspapers and periodicals, both on contemporary Crete and its archaeological remains. During this time he collected a large number of antiquities: at each village he visited he would ask if there were ‘antikes’ for sale. The first objects from Knossos in the Ashmolean’s collection were acquired in this way.3

Evans’s collecting activities were well known to the local authorities on Crete, and he does not record any attempts to prevent him from purchasing or exporting antiquities at this time. He was able to take advantage of the unstable political situation in Crete, which had gained autonomy but not independence from the Ottoman Empire. Local officials generally welcomed foreign archaeologists, particularly those like Evans who were willing to denounce the Ottoman Empire in the British press. Ottoman laws governing the export of antiquities were, seemingly, not observed. In common with many nineteenth-century scholars, Evans regarded small, portable antiquities (such as coins and seal stones) as beyond the scope of antiquities legislation, and so felt entitled to collect them in any case. Local officials were more focused on preventing new excavations, in case major antiquities such as sculptures were dug up and packed off to Constantinople Museum.

New antiquities laws came into force in 1899, passed by the government of the newly independent Cretan State. These allowed Evans to excavate at Knossos but not to export any of his finds until a change in the law in 1903. Most of the Ashmolean’s objects from Knossos were exported during the short period before Crete was unified with Greece in 1913 and excavators could request ‘useless’ objects for their collections. A few other significant objects from Knossos were donated to the Ashmolean by the Government of Greece in 1923 in recognition of Evans’s contribution to archaeological research, such as the bull-leaper fresco.

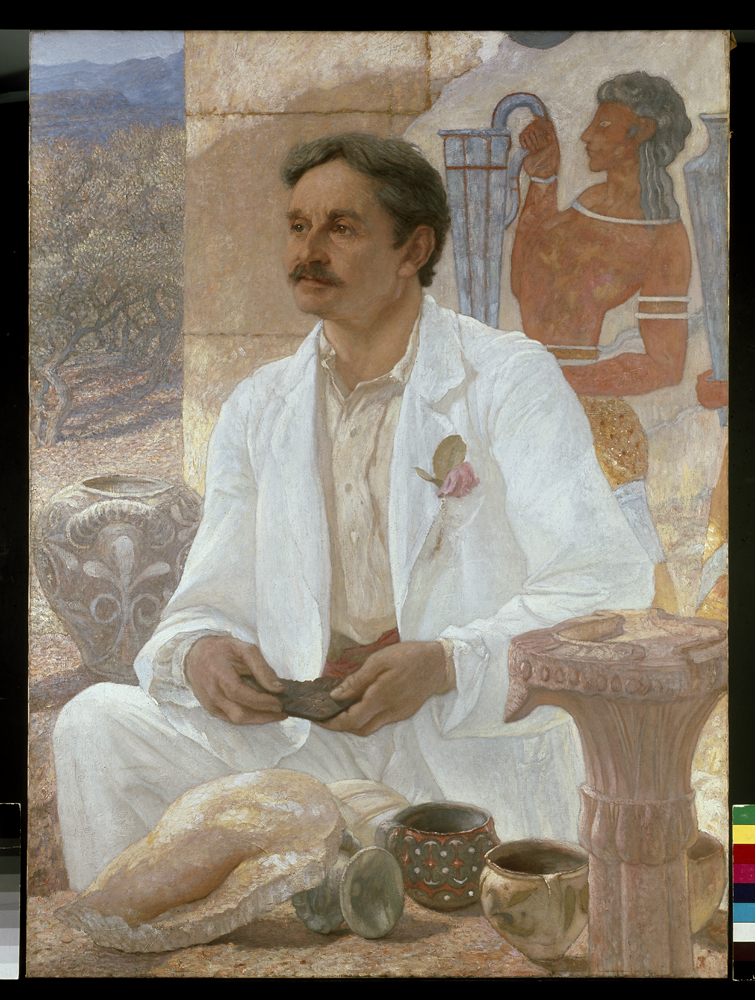

There were many important or unique objects excavated at Knossos that Evans was not able to export from Crete: these went instead to Heraklion Archaeological Museum. Instead he commissioned replicas of these which could be displayed in the Ashmolean. The plaster cast of the Throne of Minos and replica of the Priest King on display in the gallery are two examples, as well as replicas of smaller items such as the faience ‘snake goddesses’ found in the Temple Repositories in 1903. Other replicas appear in the portrait of Sir Arthur Evans that was commissioned in 1907, shortly before he stepped down as Keeper. Although it shows him among the ruins of Knossos, it was painted in London, with the replicas providing the artist, Sir William Richmond, with models for some of the finds.

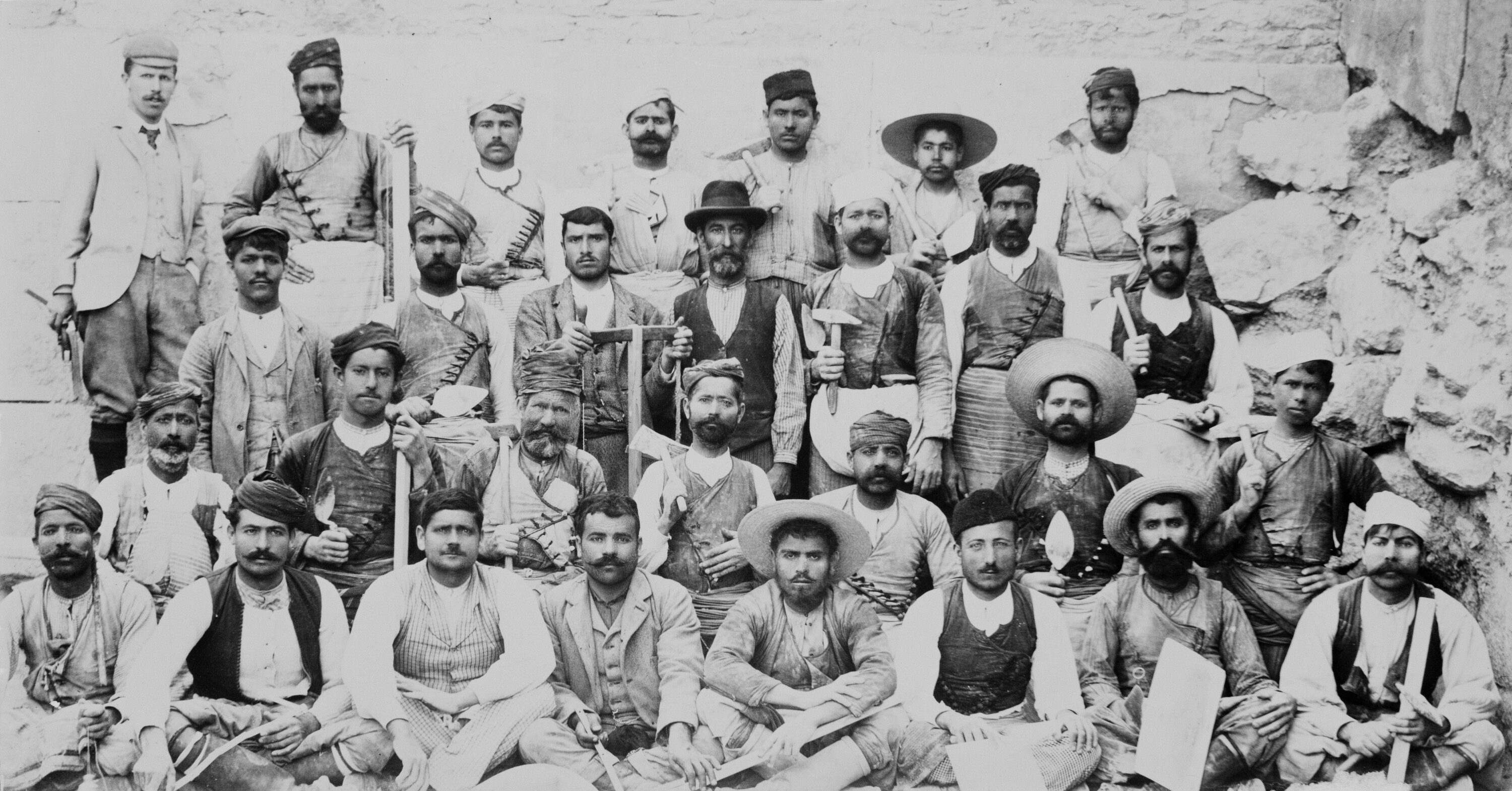

The Ashmolean was also bequeathed Arthur Evans’s archaeological archive which includes the original excavation records for Knossos. It contains over 50 notebooks kept by Evans and other members of his team, hundreds of drawings of architecture and finds, and thousands of photos. Some of the drawings of frescoes were made by Émile Gilliéron, father and son, as they tried to reconstruct the colourful fragments into complete designs. Evans drew upon all of these as he wrote up his excavations at Knossos in the massive four-volume work, The Palace of Minos, published between 1921 and 1935.4 The archive also includes early drafts and proofs of this book, and other publications by Evans. But the photos also provide a glimpse of life during excavation, including the many Cretan workers employed to work at Knossos and the excavators themselves posing for the camera.

Fragile archive items cannot be put on long-term display in the permanent gallery for reasons of conservation, but many of the objects in the collection are already available on the Ashmolean’s website, and as database records are checked, more are being added all the time.

To explore all of the objects in the Aegean World Gallery see Ashmolean Collections Online.

Notes

-

Galanakis, Yannis ed., The Aegean World: A Guide to the Cycladic, Minoan and Mycenaean Antiquities in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford and Athens, 2013 ↩︎

-

see MacGillivray, J. Alexander, Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth, London, 2000 for a recent biography of Evans ↩︎

-

Evans, Arthur J., The Palace of Minos at Knossos, 4 vols, London, 1921-1935. link ↩︎

Bibliography

- Brown 2001

- Brown, Ann, ed., Arthur Evans’s Travels in Crete, 1894–1899, BAR international series 1000, Oxford, 2001

- Evans 1921-1935

- Evans, Arthur J., The Palace of Minos at Knossos, 4 vols, London, 1921-1935. link

- Galanakis 2013

- Galanakis, Yannis ed., The Aegean World: A Guide to the Cycladic, Minoan and Mycenaean Antiquities in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford and Athens, 2013

- MacGillivray 2000

- MacGillivray, J. Alexander, Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth, London, 2000