Life in the Palace: Knossos in the Bronze Age

The Palace of Minos

Between 1900 and 1905, Evans uncovered the remains of the huge complex which he felt must be the palace of King Minos, and he adopted the name ‘Minoans’ for its occupants. He employed a team of archaeologists, local workers, architects and artists, and together they built up a picture of the community that had occupied the elaborate building 4000 years ago. The Palace of Minos, as he called it, had evidently gone through periods of wealth, destruction, rebuilding, and eventual abandonment.

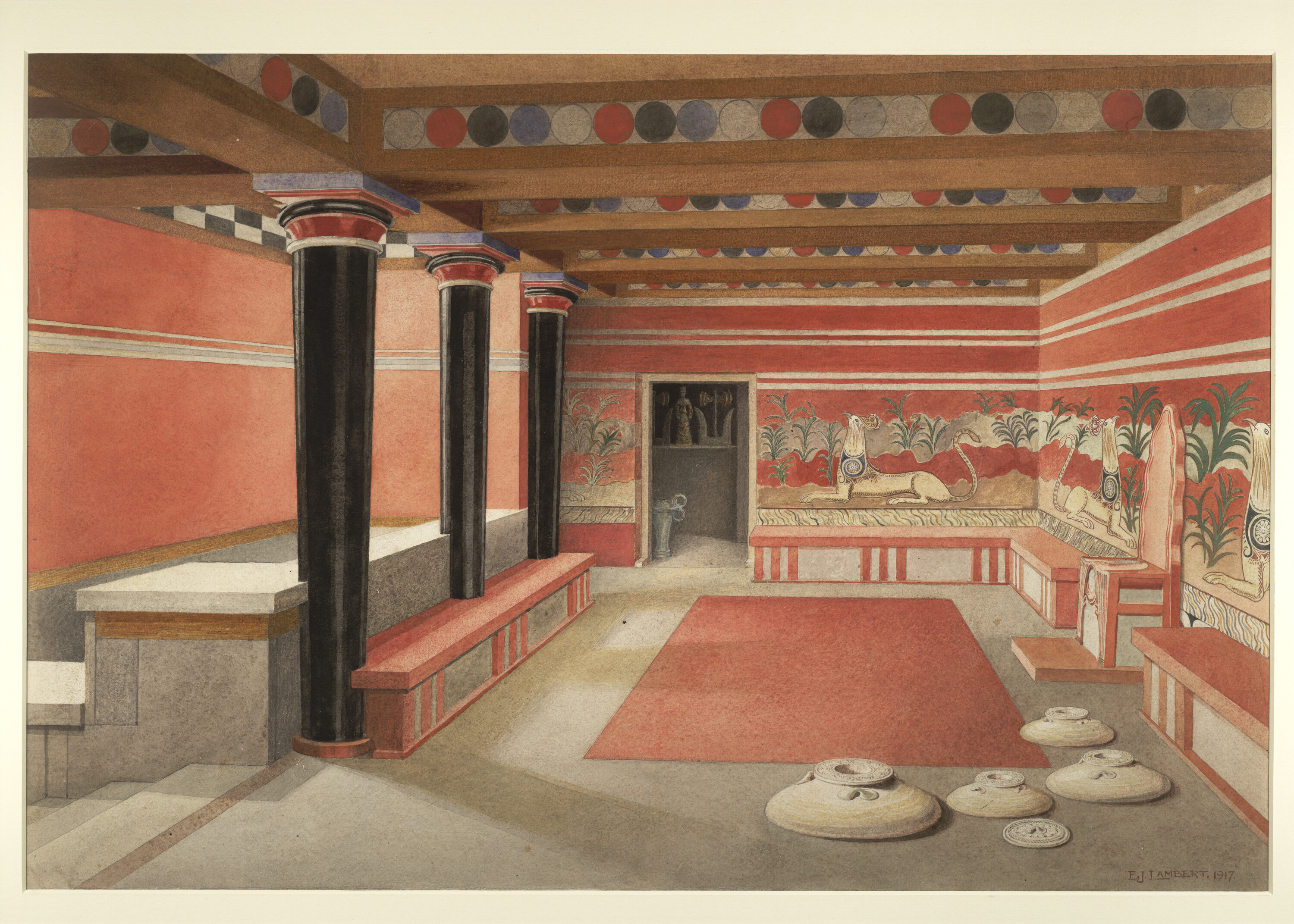

It is now difficult to disentangle Evans’s vision of the palace from the reality. Soon after excavation began in 1900, a room with a stone seat came to light. Evans regarded this as the throne of King Minos (although he originally wondered if it was meant for princess Ariadne). The ‘Throne Room’ was first reconstructed on paper and then physically. It is now is one of the most famous parts of the Palace.

Minoan Life: Eating and Drinking

Elaborate tableware and colourful frescoes are evidence of the Palace’s wealth, at least at its height. It was a place for gatherings and celebrations. Wine, meat and olive oil were produced in the surrounding area and brought to the centre for consumption. Evans and his team imagined a sophisticated, nature-loving people, whose civilisation peaked, and then went into decline. Evans suggested that the finest pottery was used by a royal family, but there is no clear evidence that one existed.

The finest pottery was known as ‘Kamares Ware’ since the first examples were discovered in nearby Kamares Cave. It was produced in the centuries after the palace was first built, around 2000-1700 BCE. The black shiny finish and thin walls seem to imitate silver, which goes black over time. Later on pottery designs were painted directly on to the surface of the clay. Some of these designs were abstract but others show plants or marine animals.

The Status of Women

Women appear prominently on frescoes and other objects from the Palace. They often wear elaborate dyed textiles indicating wealth. Weaving and dyeing were important activities at Knossos because these textiles were traded beyond the island of Crete in return for raw materials like metals. It is possible that these high-status women were important players in the manufacture and trade in textiles. Some archaeologists have even suggested that Minoan Crete was a matriarchy, with women in power. Evans, however, believed that women’s importance in Minoan society was religious, as priestesses of a mother goddess.

The Linear B tablets from Knossos were preserved by fire when the palace was burnt down in around 1350 BCE. They record an extensive textile industry in which men were shepherds and women were textile workers. By this time there was a king, ‘wanax’ in charge of the palace but it is not clear how far back this position goes because there are no historical records preserved. When Linear B was deciphered by Michael Ventris in 1952 it became apparent that all of the tablets deal with the economy of the palace.

The Bulls of Crete

Bulls crop up in several of the myths set in Crete and cattle were closely associated with the Palace of Minos. They appear on frescoes and seal-stones, and there were vessels in the shape of their heads. Sometimes they are shown with people leaping over their backs. This appears to have been part of an event like a rodeo, involving the cattle owned by the Palace. Some people have suggested that this took place in the Central Court. Evans proposed that bull-leaping inspired the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur because the images were still visible even after the Palace was destroyed.

Octopuses

Some animal images from Knossos are astoundingly lifelike and detailed.

Octopuses appear frequently – they almost become an emblem of

the Palace. One of the most

unusual facts about them is that they are shown underwater,

their eyes open – as if being watched underwater, as opposed

to looked down on from above. Evans used depictions of marine

animals to trace what he saw as the birth, maturity and

decline of Minoan art. Although few would use these terms

today it is noticeable

that earlier objects are more naturalistic. In the later

period of the Palace’s existence, the same designs – octopuses

and bulls feature frequently – become increasingly stylised.

One of the finest depictions of an octopus was carved in relief on a stone vessel known as the ‘Ambushed Octopus’. Designs like these were later transferred to pottery, particularly large jars found in the storerooms of the palace. Even after the palace was destroyed, tentacles were still used to decorate vessels.